Low hanging fruit for a mining-led economic recovery in 2021 Budget

In a speech delivered last week at the opening of the current sitting of Parliament, His Excellency Edgar Chagwa Lungu, set out very clearly that delivering an economic recovery “is the number one goal of my Government”. We can therefore expect to see the detail of the Government’s recovery plan – “the implementation of supportive policy measures” – set out in the forthcoming Budget speech, scheduled for Friday 25 September.

In broad terms, the President’s declarations should bode well for the future of the Zambian mining industry, in his commitment “to do more to promote mineral exploration, production and value addition”.

Much of the President’s emphasis was on fostering minerals diversification – gold mining, in particular – and economic diversification generally. This is both laudable and necessary if Zambia is to diminish its economic and fiscal dependency on copper. But it is a long-term objective, and one that should be pursued in conjunction with, rather than as a replacement for, growth in copper mining. Over the last 30 years, Chile has seen such an expansion in its non-mining economy that dependency on copper is at an all-time low, yet at the same time it achieved a five-fold increase in copper production, to propel it to first place in the table of copper producing countries. These are not mutually exclusive ambitions.

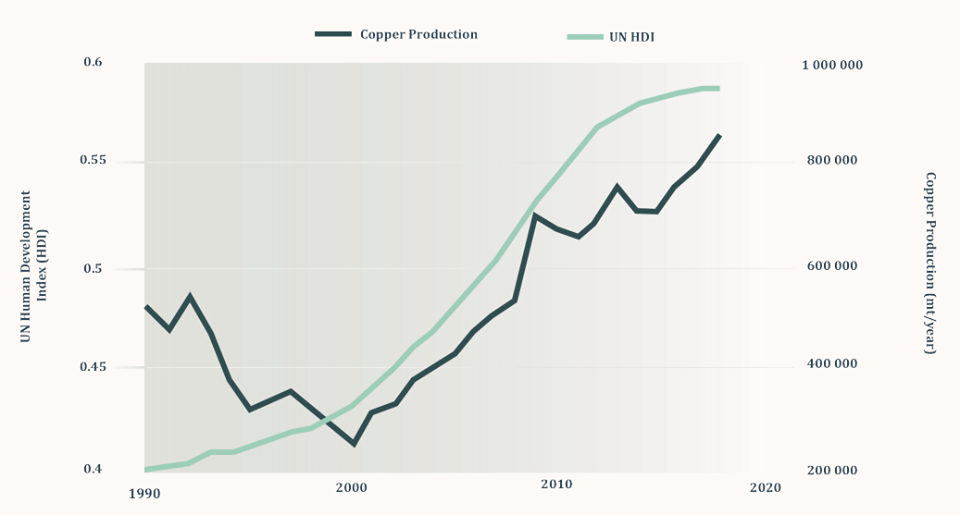

For now, though, Zambia’s economic fortunes are tied to copper. The reason for this is simple: copper accounts for well in excess of 90% of all mineral exports, which in turn account for approximately 80% of all Zambia’s exports. Copper is therefore the nation’s foreign exchange earner, just as it is the major source of foreign investment. If there is to be any significant immediate boost to the economy, it will need to come through inward investment, and only major copper projects presently offer the scale of investment necessary to push the economy into growth. It has always been so; periods of growth in Zambian copper mining have gone hand in hand with growth in national GDP, and improvements in the Human Development Index – proving that when mining flourishes, so does Zambia, and so do its citizens.

But it is one thing to acknowledge the truth of the matter, and another to act on it. For years now, relations between the mining industry and Zambia’s Government have been turbulent and adversarial, characterised by a profound distrust of each other’s perceived self-serving intentions.

At this juncture, however, both desperately need a mining recovery, so that each can take full advantage of the high demand for copper that the world’s new industries are creating. So, what can be done?

Periods of growth in Zambian copper mining have always gone hand in hand with growth in national GDP, and improvements in the Human Development Index – proving that when mining flourishes, so does Zambia, and so do its citizens.

Of all the gripes that the mining industry has with the present taxation regime, one element in particular stands out. It appears technical, and can get lost amongst the many other aspects of mineral royalties – but it makes all the difference to investors.

It is this: since 2019, mineral royalty payments are no longer a deductible expense for the purposes of calculating corporate income tax. So, what exactly does this mean?

To put it simply, a mining company pays a royalty on a monthly basis, which is a percentage of its sales. If the price of copper is $6 000 per tonne, and the royalty rate is 7.5%, a mining company will receive a maximum of $5 550 for that tonne, with the balance (i.e. the $450) being paid over to Government as a royalty.

Non-deductibility means that when calculating income tax, the Zambia Revenue Authority will act as if the company retains the full $6 000. The company is therefore taxed on a sum (i.e. the $450) that has already been paid over to the Revenue Authority as a royalty. This amounts to double taxation.

Quite apart from the ethics of it, this one measure alone dramatically changes the effective tax rate, handing almost all the returns from mining to the State.

Two of our neighbouring countries have recently experimented with this measure – Namibia and Zimbabwe – and both have now definitively reversed course.

After 18 months of extensive consultations with the mining industry, the Namibian Government in the Budget announcement of 27 May 2020, decided to shelve non-deductibility. In the words of Namibian Finance Minister, Ipumbu Shiimi:

“The proposal, previously announced, to disallow tax deductibility of royalties for mining entities is hereby withdrawn. This is to encourage investor confidence and economic agents [i.e. mining companies] to explore, produce and reinvest in Namibia”.

“Fortunately, in Namibia, non-deductibility was never actually progressed into law. Instead it was brought in as a tax proposal in the Income Tax Amendments Bill in September 2018, and tabled for discussion with the mining industry through the Chamber of Mines. Even so, that was enough to stop exploration and mining investments dead in their tracks,” says Veston Malango, Chief Executive of the Chamber of Mines of Namibia.

“The problem is that non-deductibility decimates the net present value (NPV) of mining projects by almost 50%, meaning that they are no longer viable. We did the sums and engaged Government with actual illustrations of effects of non-deductibility for each mine; a gloomy picture for the entire industry emerged.”

Mr Malango describes an 18-month process of close engagement with the Namibian Government. “The issue is always ‘what is a fair share’, and in this we were able to show that non-deductibility produced an unfair outcome for existing investors, and frightened all others away. We opened our books and demonstrated to Government the devastating effect if the tax proposal was to be enacted into law.

With the unattractive NPV, there would be no new mining investments, no investments into existing mines (to extend life of mines) and exploration would come to a standstill because viable new mineral discoveries would not proceed to a mine under the non-deductibility tax proposal. In summary, the growth and sustainability of the mining industry would be jeopardised. Hats off to the Namibian Government – they do listen if you have a valid argument backed by figures; we were able to make our case to Government at all levels including to the High-Level Panel on the National Economy (HLPNE) appointed by the President. The HLPNE organised the economic summit last year, where the entire government, from the President down, was present.

“At the stroke of the Government’s pen, much needed investments into exploration and mining are pouring into Namibia. I wish the same could happen in Zambia, so that mining can help rebuild the economy, especially now with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

At this summit, Government acknowledged the challenges posed by the non-deductibility clause and announced its suspension. With this final announcement in May’s Budget speech, the whole concept has now been decisively shelved. At the stroke of the Government’s pen, much needed investments into exploration and mining are pouring into Namibia. I wish the same could happen in Zambia, so that mining can help rebuild the economy, especially now with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

According to the Chamber of Mines of Namibia, since the withdrawal of the non-deductibility proposal in late May, no less than five major mining investments have been announced, including the development of two underground gold mines as extensions of current open pit operations, an extension of the Rosh Pinah zinc mine, and a conversion of Skorpion’s zinc refinery into a toll refinery facility. Debmarine Namibia is also now adding a new ship to its fleet of marine diamond vessels, at a cost of N$ 7 billion (approximately US$ 429.5 million). According to Mr Malango, the contractor that is developing one of the underground mines has come “all the way from Mufulira”, illustrating how Zambia’s mining talent is itself a great export for the nation, and a reputational asset.

Sokwani Chilembo, Chief Executive Officer of the Zambia Chamber of Mines, is emphatic that the Zambian mining industry would welcome a similar result, and needs to see a clear signal in the coming Budget that the Government is serious about investment. “Exploration activity is around a tenth of the levels of a decade ago, and sustaining capital – the money to keep our mines going – has dried up since last year. We have two members – Kansanshi and Lubambe – that want to expand their mines. To give some idea of scale, their combined project costs would be in the order of 10% of national GDP. But investors and financiers just won’t give the green light under the current regime. Doing away with non-deductibility is the obvious place to start, and we must start before it is simply too late to turn things around.”

One of the members Mr Chilembo was referring to is First Quantum Minerals, who this week announced a 70% increase in the now identified mineral reserve of Kansanshi mine, which has opened the possibility of the long-awaited S3 expansion project at the mine.

According to John Gladston, Assistant General Manager at Kansanshi, “it is a mis-characterisation to only talk about S3 as an expansion; S3 is also very much about extending the life of mine – at an increased level of production – into the future. If we don’t do this project, then production at Kansanshi will drop significantly in the coming years, as will our tax and royalty contributions.”

Some of First Quantum’s forecasting has suggested that Kansanshi’s tax contributions with the S3 expansion project could be up to 45% higher over the five-year period from 2024-2028, than if the project does not go ahead.

“We are absolutely committed to Zambia and our operation at Kansanshi, but we need help from our partners in Government to get this project over the line. Doing away with non-deductibility is the best evidence that they could give, to signal that change is in the air.”

![]()